“How can a man who becomes the leader of his country through outside help and influence just as the cheeks become radiant because of diamond ear-ring [1], as the Burmese saying goes, hope to be able to do much for his country?”

Ne Win, Myanmar’s military army general and dictator

Myanmar experienced yet another military coup in 2021 when General Min Aung Hlaing seized power, an event that closely mirrors the 1962 coup. Min Aung Hlaing declared, “We shall build a genuine and disciplined democratic system,” echoing Ne Win's 1962 assertion that parliamentary democracy was unsuitable for Myanmar: “We will not get very far if we are stuck with the parliamentary system where several political parties compete for power.” Both leaders claim to know what is best for the country, viewing democracy as either something to be domesticated or something to be entirely removed.

Unlike the internal military coup of 1988, which did not alter Myanmar's political system, the coups in 1962 and 2021 set the country on an unfavourable path, depriving its people of fair governance and freedom. Ne Win and Min Aung Hlaing both share a belief that democracy is not a viable option for Myanmar. They both have a deep-seated disdain for foreign influence in the country. As staunch nationalists, they are both committed to upholding the main goal of the military: to maintain Myanmar’s unity. This essay explores the lives and thoughts of Ne Win and Min Aung Hlaing to shed light on the enduring legacy of their leadership and their impact on Myanmar's political landscape.

Figure 1 Myanmar people protesting against the 2021 coup (MgHla – Wikimedia Commons - CC BY-SA 4.0)

As a disclaimer, information about Myanmar’s military (known as the Tatmadaw တပ်မတော် or Sit-tat စစ်တပ် [1]) is scarce and difficult to obtain due to the military's secretive nature. Martin Smith, as cited in Selth, described the military as “a state within a state” because it is “far removed from mainstream Burmese society”. Therefore, providing a comprehensive analysis, even of its well-known members, is challenging. One clear aspect of the military, especially its top officials like Ne Win and Min Aung Hlaing, is their obsession with preserving the country’s sovereignty. The military has three main goals, known as “Our Three National Causes”, which are: non-disintegration of the Union; non-disintegration of national solidarity; and perpetuation of national sovereignty. These goals have heavily influenced both Ne Win’s and Min Aung Hlaing’s actions and decisions.

Ne Win’s: Obsessed with Maintaining Unity

"History repeats itself," they say, and in the case of Myanmar, this is evident. Myanmar has experienced several coups in its short but tumultuous history. After gaining independence from the UK in 1948, Myanmar underwent three coups: in 1962, 1988, and 2021. The 1962 coup was orchestrated by General Ne Win, who fought for the country’s independence against both the British and the Japanese and was a member of the nationalist organization known as the Thaksins (which also included General Aung San).

Figure 2 General Ne Win with the Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in 1964 (人民画报 - Wikimedia Commons)

Following Myanmar's independence, Ne Win joined the army and built a significant career, becoming close to former Prime Minister U Nu. In 1958, as the political situation in the country became chaotic, U Nu handed power to Ne Win. The unrest was fuelled by U Nu’s decision to make Buddhism the state religion, angering minorities, and granting more freedom to ethnic states, which destabilized the central government. Believing it was better to let Ne Win manage the situation, U Nu appointed him as interim PM of the Caretaker Government. Ne Win promised to hold elections in 1960 and return power to the civilian government. He kept his promise, and after U Nu was elected, he handed back power. However, two years later, in 1962, Ne Win orchestrated a coup, reportedly bloodless, and took place overnight. Although not unexpected, it was staged in secrecy, so much so that even the Deputy Commander of the armed forces, Brigadier General Aung Gyi, was not informed of it until the following morning.

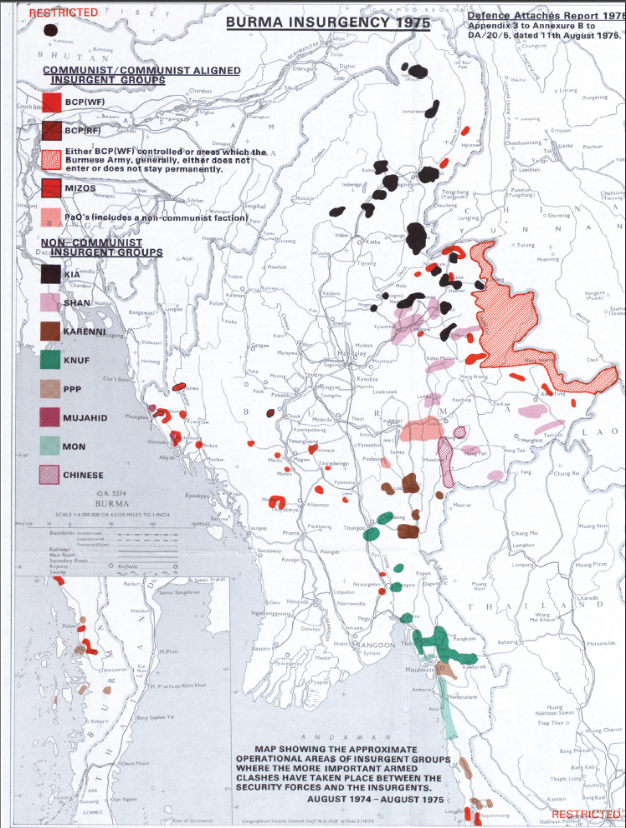

Figure 3 Myanmar insurgency in 1975 (Taylor, 2016, p. xxvi)

Figure 3 Myanmar insurgency in 1975 (Taylor, 2016, p. xxvi)

Ne Win was a fervent nationalist, uninterested in any ideology or religion beyond his goal of keeping Myanmar united, regardless of the methods used. He was known to say: "The strength of the country is in the country." His “Burmese Way to Socialism” was devoid of coherent ideology, as he reportedly disliked reading political theories. Martin Smith described it as a "mishmash of selected Marxist, Buddhist, and nationalist principles." Ne Win opposed democracy, stating, "We will not get very far if we are stuck with the parliamentary system where several political parties compete for power," which led him to assert that a one-party system was the only viable option for Myanmar.

Ne Win was also wary of foreign influence, favouring autarky and isolationist policies. Upon gaining power, he severed many of Myanmar's international contacts and refused foreign aid to avoid interference from other countries. During his tenure, Ne Win increasingly embraced isolationist policies, driven by his growing paranoia about foreign influences in Myanmar’s domestic politics. He argued that countries accepting foreign aid often faced negative consequences, reinforcing his belief that Myanmar should be self-reliant. Ne Win maintained that Myanmar could thrive independently, stating, "We can, after all, carry on by ourselves. In fact, we have been getting on by ourselves, practicing strict economy." A CIA report titled “Burma under Ne Win,” written in 1966 and released to the public in 2006 described Ne Win’s isolationist policies, noting: “Under Ne Win, Burma’s traditional policy of neutralism and non-involvement has been pushed almost to the point of isolation from world affairs.”

Ne Win was obsessed with maintaining unity amidst ethnic fragmentation and political tensions. As ethnic armed groups increasingly sought autonomy and communist groups insisted on maintaining control of their forces, Ne Win grew more fearful of Myanmar's potential "balkanization." This fear drove him to tighten his grip on the country to prevent it from becoming another battleground for Cold War powers, as had happened in Vietnam and Korea. Ne Win stated: “The outside does not care for us one bit. We also are not working for their affection.”

It is important to note that Myanmar politics is highly personalized, and Ne Win’s reported jealousy towards Aung San, a revered nationalist icon, adversely impacted national policy and shaped both his and the military regime’s attitude toward the opposition.

Min Aung Hlaing: On the Footsteps of Ne Win

Min Aung Hlaing was born in southern Myanmar to a government employee. He joined the military as a cadet, and after three attempts, he entered the Defence Services Academy. Although he did not particularly stand out, he gradually climbed the military's social ladder. In 2009, he was promoted to Commander of the Bureau of Special Operations-2. In 2010, he became Joint Chief of Staff, and in 2011, he succeeded Than Shwe as Commander-in-Chief.

He played a significant role in various military operations, including clamping down the Saffron Revolution in 2007, fighting against ethnic armed groups in Shan state in 2008 and his involvement in the Rohingya genocide in Rakhine state in 2017.

During the liberalization and opening up of Myanmar beginning in 2011, Min Aung Hlaing became more publicly involved in politics but was not very cooperative with the civilian government. He ensured that the military retained 25% of parliamentary seats, despite Aung San Suu Kyi's attempts to change this. Like Ne Win, Min Aung Hlaing believed in the importance of the military's involvement in politics, stating that the military works for “the interest of the country [...] performing the duty of national politics” and that “we, the military along with the people, will respect and safeguard the constitution which is the lifeline of the country.”

He is reluctant to relinquish the military’s grip on Myanmar, driven by fears of the country disintegrating due to ethnic tensions. In a rare 2015 interview with the BBC, he stated that the military will remain involved in Myanmar’s politics until peace talks and ceasefires have been achieved with all ethnic groups. Additionally, he underscored the importance of people understanding that the military is there for them, saying: "They'll [Myanmar people] see the military is defending the interests of the people and implementing the interests of the people and defending against threats to the country."

The same Ne Win’s obsession with avoiding the disintegration of Myanmar was evident when the military carried out the coup in 2021, claiming that the national election was fraudulent. Min Aung Hlaing argued that not addressing this issue could lead to a disintegration of national solidarity. He wanted to avoid a landslide victory for the National League for Democracy (NLD), which would have further eroded the military’s power. Furthermore, Min Aung Hlaing is paranoid about external influence and focused on maintaining stability within the country. At the Armed Forces Day parade in 2024, he stated, “The military, police force, and people's militia are working to restore peace and stability” and emphasized the importance of unity between the military and the people. He also claimed that “some powerful nations” were interfering with Myanmar’s domestic politics by arming ethnic armed groups, though he provided no evidence. This obsession with external interference closely mirrors Ne Win's time in power.

Figure 4 Min Aung Hlaing in June 2017 (Vadim Savitsky, mil.ru - CC BY 4.0)

Finally, Min Aung Hlaing’s coup, like Ne Win’s, took the country by surprise. While it was not unexpected within the military, as Min Aung Hlaing needed the support of other generals to carry it out, the general population did not expect it. Another similarity is Min Aung Hlaing’s dislike of Aung San Suu Kyi – similar to Ne Win’s jealousy of Aung San – playing a significant role in his decision to stage the 2021 coup. Scholars, like Selth, also highlighted Min Aung Hlaing's personal objectives as likely reasons, including safeguarding his wealth and position should the opposition gain excessive power.

Conclusion: Similar Approaches

The colonization of Myanmar and the subsequent centralization and bureaucratization of the country created strong divisions along ethnic lines, leading to protracted guerrilla warfare between the central government and ethnic minorities in border areas. In such a divided country, a sense of unity has been difficult to achieve. This environment facilitated the rise of a centralized military organization aimed at preventing the secession of various parts of Myanmar and keeping the country intact. In fact, the military's primary objective is to protect “Myanmar’s independence and sovereignty”, which is the rationale behind Ne Win’s and Min Aung Hlaing’s actions.

Ne Win and Min Aung Hlaing both were raised in an environment where the military is thought to be the ultimate arbiter of Myanmar, believing that they know better what political system is suitable for the country. After his coup, Ne Win outright rejected democracy, stating it was unsuitable for Myanmar and advocating for a one-party system where all parties would be consulted but not compete. Similarly, Min Aung Hlaing claimed that the democracy Myanmar had experienced until then was flawed, asserting that the military would ensure “a genuine and disciplined democracy.” By using the term "genuine," he implied that the previous democratic system was incorrect and needed to be reshaped to better suit Myanmar's conditions. Both held personal grievances against Aung San and Aung San Suu Kyi, that shaped their approaches to dealing with the opposition. They both disdained outside influence and tried to insulate Myanmar from the outside world and they were both adamant about keeping the military involved in politics to protect the country's sovereignty. Most importantly, Ne Win and Min Aung Hlaing overthrew a relatively democratic system, setting the country on a path of self-destruction.

Federica Cidale is a PhD student in International Relations and Asian studies at Palacký University Olomouc in the Czech Republic and CEIAS Research Fellow. She holds an MA from Rijksuniversiteit Groningen in the Netherlands and has studied and worked in Italy, Belgium and Japan. Her main research delves into the growing influence of cybertechnologies on international politics.

Furthermore, her research interests extend to Japan's domestic politics, East Asian security, the Indo-Pacific region, ASEAN – particularly Myanmar – and non-Western state systems such as Tianxia and Mandala. Federica is also involved in the EU-funded project “The EU in the Volatile Indo-Pacific” (EUVIP; 2023-2025).

You can reach me at: federica.cidale01@upol.cz

[1] The proverb in Burmese is စိန်နားကပ်အရောင်နဲ့ပါးပြောင်နေတယ်.

[2] The term Tatmadaw (တပ်မတော်) has traditionally been used in scholarly and journalistic reports to refer to Myanmar’s military. However, due to moral considerations, some advocate for a change, as the particle Daw (တော်) means "Royal," which critics argue whitewashes the military’s crimes and is undeserving for such an organization. On the other hand, the term Sit-tat (စစ်တပ်) simply means "military" in Burmese.