For Myanmar nationals who have received study grants or work opportunities in some European countries, the most challenging aspect of the visa application process is to obtain a criminal clearance letter required by the embassy.

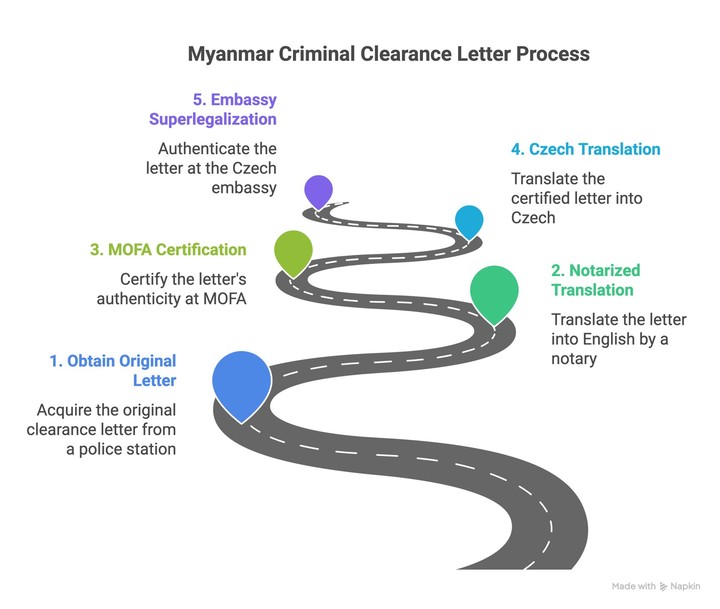

Obtaining and authenticating the criminal clearance letter for visa purposes is a complicated five-step process: first, to receive a criminal clearance letter from a police station in Myanmar; second, to arrange a translation (from Burmese to English) with an authorized notary service; third, to obtain a "Certification of True Copy" of both the original criminal clearance letter and the notarized translation from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), with their copies bound and stamped in the upper left corner; fourth, to translate the document into the relevant official language (in this case to Czech); and finally, to undergo superlegalization at the relevant (Czech) embassy. One can proceed with the visa application only after completing this five-step-process.

Diagram 1: Processes of Obtaining and Authenticating the Criminal Clearance Letter for Visa Purposes

Since getting this criminal clearance letter from Myanmar, especially for those no longer residing in the country, is so complicated, it ends up hindering many Myanmar individuals from pursuing academic or professional opportunities in Czechia, leading them to seek alternatives in other countries or even to abandon their pursuits, resulting in a systematic disadvantage compared to other nationals in the long term.

Since getting this criminal clearance letter from Myanmar, especially for those no longer residing in the country, is so complicated, it ends up hindering many Myanmar individuals from pursuing academic or professional opportunities in Czechia, leading them to seek alternatives in other countries or even to abandon their pursuits, resulting in a systematic disadvantage compared to other nationals in the long term.

Particularly after the 2021 coup in Myanmar, the situation has become increasingly challenging and is evolving on a daily basis. The requirement to obtain a criminal clearance letter from police stations under the military regime control, followed by certification from the regime-controlled Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), may pose a risk to the safety of applicants and their family members.

Myanmar’s youth and intellectuals, who participated in the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) by exercising their civil rights, have been perceived as criminals by the regime. As a result, they encounter security risks when seeking a criminal clearance letter from police authorities. The regime has also detained three MOFA officials providing notary services to civilians associated with the CDM.

Even if an applicant manages to obtain a criminal clearance letter – whether through the discretion of local, bribery, or assistance from a middleperson – it must still be certified at a MOFA office (in Yangon or Naypyitaw). If the applicant cannot appear in person, a family member must be present. The fear of potential detention throughout this process is akin to psychological torture for both the applicant and their representative.

Moreover, for Burmese nationals living abroad, accessing this document is especially complex and burdensome. Additionally, if requested, applicants must provide police clearance from any country where they have resided for over six months in the past three years.

As a Myanmar national and recipient of a prestigious postdoctoral fellowship in Czechia, I would like to share the challenges I faced during the visa application process. I have resided outside Myanmar for over a decade and hold permanent residency in another country in Asia. Furthermore, also my parents no longer reside in Myanmar, making it difficult to return there solely for the purpose of obtaining official documentation. For some individuals, returning to Myanmar is currently impossible.

Given the regime's active recruitment of youth into the military, the risk of being detained or forcible conscripted upon return is too great. This article urges relevant European authorities to reconsider the criminal clearance requirement and to implement a fair and effective alternative that fulfills policy objectives while reducing the burden on applicants.

The Criminal Clearance Letter in Myanmar: The Illusion of Verification

The requirement to submit a "Criminal Clearance Letter" for visa applications is well-intentioned. It is of paramount importance for a country to ascertain whether an individual applying for a visa has a criminal background or is a criminal. However, one prevalent issue observed across various organizations, whether local, national, or international, is the tendency to concentrate on the procedural aspects rather than the actual circumstances. This requirement, particularly during the ongoing conflict, for Myanmar nationals raises the question of whether this can provide the actual records of one's history for a few reasons.

Firstly, Myanmar is in the process of developing a centralized database. The primary purpose of this database is not to track criminals, but rather to politically control the populace (e.g. individuals who participated in the CDM and resistance members). It is less probable that all police stations throughout Myanmar have comprehensive details on criminal records, particularly details of those who have resided abroad for decades might also be lacking in the database. Even where such systems exist, the limited telecommunication and internet access in many regions complicate verification processes during these turbulent times.

Secondly, the ongoing intense armed conflicts have forced many individuals to flee their homes, resulting in their relocation to IDP camps, refugee camps, or other areas where their data is not systematically registered, transferred, or accessible. Consequently, even if a police station issues a Criminal Clearance Letter, it cannot ascertain the individual's complete criminal history or guarantee their non-criminal status.

Furthermore, during this period of instability in Myanmar, cases involving criminal activity may be resolved through bribery of officials. Therefore, regardless of whether an individual can provide a Criminal Clearance Letter, the document remains merely a piece of paper.

There are also ethical concerns when a criminal clearance letter from the regime-controlled police stations and the MOFA is a requirement. Along with the military (Tatmadaw), particularly the Myanmar Police, have been accused of numerous crimes against humanity, such as bombings, shelling, arbitrary detention, torture, killings, shootings, beheadings, and the burning of civilians. The irony of civilians needing to request a criminal clearance from those accused of such crimes is comparable to asking for a morality certificate from the devil.

The Superlegalization Process: Risk, Inequality, and Red Tape in Conflict-Era Myanmar

The whole process involves five steps (before the actual application for the visa). While most of these steps can be handled by a representative, certification at the MOFA, step number three, requires the applicant’s presence – or, if that is not possible, the presence of an immediate family member.[1] Fortunately, in my case, my younger sister, who happened to be in Naypyitaw at the time, was able to assist with the certification process at the MOFA office there. Not everyone has access to such an opportunity.

The process at MOFA requires the presentation of the original national identity card, not a copy, of the applicant along with the family registration card. In my case, I had to send my original national identity card via express mail, and my parents, living in another country, had to send our family registration card to my sister. These requirements pose numerous challenges and risks, such as the potential loss of original documents during delivery, especially with the notoriously unreliable postal services in Myanmar, or the possibility of my sister being detained for further interrogation for unproven, suspicious reasons (e.g., my mother was a government employee before the 2021 coup but left her job to join the CDM, and I also refused to work under the regime).

In the Yangon MOFA office where traveling from other parts of the country is more convenient than Naypyitaw, people must wait for months to receive a token to present themselves for this process (while in the Naypyitaw office it takes three days to a few weeks). Given the police record document's 180-day validity, it is not ideal to spend months waiting for this certification and a stamp.

Also, the ongoing civil war in the country makes traveling from one location to another fraught with challenges due to transportation blockades and the risk of encountering armed clashes. Traveling to Yangon or Naypyitaw from other areas also incurs significant financial costs. The requirements have effectively disadvantaged individuals from rural or remote areas who lack social and financial capital, causing them to fall further behind in accessing educational and job opportunities compared to those from middle and upper classes.

In the last, fifth step of the process, when submitting documents to the relevant embassy in Yangon (in this case the Czech embassy) for superlegalization, the notarized English copy and the Burmese original must be bound together with a MOFA stamp in the upper left corner. If this requirement is not met – or if the copies are unbound for reasons like making a sworn translation, as in my case – the embassy will reject them. This then forces applicants to return to MOFA, often requiring a long wait or restarting the entire process, since the original Burmese document is retained and not returned. In my case, the notary erroneously placed the stamp on the binding corner – where the MOFA stamp is required – requiring the entire process to be restarted.

The superlegalization (step number five) takes about a week. In my case, my sister was no longer available to assist, but fortunately, a friend was able to represent me at the embassy for the superlegalization process, collecting the documents, and sending them to me via express mail.

If an applicant has the necessary social and financial resources, the entire process – from requesting a criminal clearance letter at the police station to completing the final superlegalization step – can typically be finished in about one month, especially when handled through the Naypyitaw office. In my case, excluding a previous failed attempt due to an incorrect stamp, the process took 35 days. However, when including that earlier attempt, I spent a total of 93 days. This duration does not account for the time required for the visa application.

During periods of intense civil conflict, the processing timeline may be affected by various factors, such as being caught in the midst of armed clashes while traveling, being detained (individuals or the express bus/vehicle) by armed groups at security checkpoints, or the closure of the intended MOFA office due to conflict or natural disaster. The entire process – especially on the Myanmar side, where I haven’t lived in over a decade – was psychologically exhausting. I couldn’t sleep peacefully until all the necessary documents were in hand – and the embassy where I intended to apply accepted them without requesting additional information. I also incurred significant financial costs – covering daily expenses and transportation fees for my friend and sister while they assisted with the process.

Conclusion: A Call for Rethinking Criminal Record Requirements

In conclusion, although the policy of mandating a criminal record extract from visa applicants is well-intentioned, it is crucial for the relevant authorities to thoroughly assess its actual effectiveness in the case of Myanmar.

In Myanmar, this document does not accurately represent an individual's history and raises ethical issues. Applicants, including their representatives, face considerable risks, time, and financial burdens for a document that is essentially just words on paper, lacking genuine value.

This requirement disproportionately impacts those who are economically and socially disadvantaged, further reinforcing systemic inequalities. On the other hand, individuals with financial and social resources may not experience the same strain, revealing an inherent bias.

Additionally, this requirement may hinder applicants from pursuing opportunities in Czechia, prompting them to consider alternatives elsewhere, or causing them to fall behind other nationals.

I urge the relevant authorities to reevaluate this requirement, which neither achieves its intended purpose nor serves the interests of the applicants. A more fair and effective system is necessary, one that aligns with policy objectives while easing the burden on applicants.

[1]As the situation in Myanmar continues to evolve daily, the associated requirements are also subject to frequent change. A friend noted that, about a year ago, anyone could represent the applicant when applying for a “Certification of True Copies.” However, the regime has since introduced increasingly stringent requirements, and it remains uncertain what further restrictive measures may be imposed in the future.